A Critical Examination of the Claim That “Muslims Are Also Killed” as a Response to the Genocide of Christians and Indigenes/Natives of Nigeria

by

Barr. John Apollos Maton

20th December 2025

INTRODUCTION: THE DANGEROUS SIMPLICITY OF FALSE BALANCE

In every conflict marked by sustained violence against a particular group, there emerges a predictable rhetorical maneuver: false equivalence. When the subject of mass killings of Christians is raised, especially in locations plagued by sectarian violence, a familiar refrain is deployed; “Muslims are also killed.” This statement is often presented not as a call for universal justice, but as a rhetorical shield meant to dilute, deflect or delegitimize the claims of targeted persecution. The purpose is not to mourn all victims or empathise with survivors, but to suspend moral urgency, silence advocacy and neutralize accountability.

The unanswered questions by the protagonists of “Muslims are also killed” despite repeatedly asking is a simple but uncomfortable one: Who is the culprit of the gangster killing spree in Nigeria?

When Christians are being killed systematically, and the response is that ‘Muslims are also killed’, then logic demands further inquiry; Who is killing whom? Under what circumstances? With what intent? And in whose name? These are not questions of sentiment but of truth, evidence and responsibility. To refuse to ask these questions is not neutrality, it is complicity in obscuring reality.

DEFINING GENOCIDE AND TARGETED VIOLENCE

Genocide is not defined merely by the existence of death inflicted by gangster and selective violence; it is defined by domestic cum international law based on observed pattern, intent and identity. The killing of members of a group because they belong to that group constitutes a crime of a fundamentally different moral and legal category than killings resulting from crime, collateral conflict or intra-group violence (eg. arising from boundary disputes).

When Christian communities are attacked and killed in their bedrooms while asleep, in their villages, churches, farmlands and market places, often without reprisal aggression, the issue is not about quantum numbers alone. It is targeting. It is the selection of victims based on ethnoreligious identity. It is the destruction of lives, livelihoods, properties, sacred spaces and communal continuity. To respond to such evidence with the vague assertion that “others are also killed” is to evade the definition of genocide entirely.

No serious moral framework allows the suffering of one group to be dismissed simply because suffering exists elsewhere.

THE “MUSLIMS ARE ALSO KILLED” ARGUMENT: A LOGICAL AUTOPSY

At first glance, the claim that “Muslims are also killed” appears humane. Who would deny that all lives matter? Yet when examined closely, the argument collapses under its own contradictions.

If Muslims are also killed, then by who and why? Are they killed by Christians acting collectively? Are Christian militias invading Muslim villages? Are churches mobilizing armed groups to attack mosques? What is the evidence, public declarations or ideological manifestos supporting such claims?

The answer, based on available historical records including data, is unequivocal: No. Christians, as a collective religious group, have not organized, celebrated, or justified mass attacks on Muslims in the territorial locations under discussion. There are no evidential records and data of Christian mobs chanting religious slogans while burning Muslims or their settlements, worship places, livelihoods and markets. Nor are there such records and data of sermons by Christian clerics calling for the extermination of Muslims. No coordinated religious campaigns encouraging violence or crime. This absence of evidence is not accidental. It reflects a fundamental asymmetry that the claims in “both sides” narrative refuses to confront.

THE QUESTION OF EVIDENCE: RECORDINGS, ADMISSIONS, AND PATTERNS

One of the most damning aspects of modern conflicts is that they are often documented by the perpetrators themselves. Videos, photographs, statements and social media posts have become tools of intimidation and ideological signaling.

In the cases under discussion on genocides against Christians, there exist repeated instances where attackers openly identify themselves, invoke religious language, and frame their violence as justified or divinely sanctioned. These are not anonymous accidents. They are ideological acts. When individuals proudly record and disseminate evidence of their crimes, they remove ambiguity about intent.

By contrast, there is no comparable archive of Christians collectively boasting about religiously motivated mass violence. This is not a claim of moral perfection, but of empirical reality. Individual crimes exist everywhere. Organized religious extermination by Christians in these contexts does not exist. Thus, when Muslims are killed, the crucial question remains unanswered by deflection: who killed them, and why?

COLLATERAL DEATH VERSUS TARGETED EXTERMINATION

Another deliberate confusion lies in the failure to distinguish between collateral deaths and targeted killing for extermination. In territorial locations affected by insurgency, banditry, and terrorism, civilians of all identities may tragically die. But not all deaths are equal in meaning.

When a Christian farmer is killed because his farmland is trespassed and crops ravaged, his homestead is seized, his church burned, and his village erased, the motive is clear. When worshippers are massacred during religious services, the symbolism is undeniable. When survivors are told to convert, flee, or die, the intent is explicit.

If Muslims are killed in clashes between armed groups, criminal networks, or internal disputes, those deaths are tragic and demand justice, but they do not negate evidence of a parallel, targeted campaign against Christians. Conflating the two is not analysis; it is obfuscation. Yet, the question remains; who killed the Muslims and why?

WHY THE FALSE BALANCE IS POLITICALLY USEFUL

The insistence on “both sides suffer” serves powerful political interests. It allows governments to avoid naming perpetrators. It enables international actors to maintain diplomatic comfort. It shields extremist ideologies from scrutiny by dissolving them into generalized chaos.

Most dangerously, it gaslights victims including survivors. It tells survivors that their suffering is exaggerated, their fear misplaced, and the death of their kinsfolk is a mere statistic in a symmetrical tragedy. This rhetorical strategy does not promote peace—it perpetuates silence. History shows that genocide is rarely denied outright in its early stages by the perpetrators and supporters of the evil. Instead, it is minimized, relativized, pacified and buried under calls for patience and restraint, so the voices of the victims are lost and the true agenda hidden. In Plateau State and many parts of Nigeria, the strategy denying cries against this Genocide is to have even the government misnormered it as being “Insecurity” or the infamous “Farmer-Herder Clash”.

THE MORAL FAILURE OF SILENCE AND DEFLECTION

There is a profound ethical failure in responding to cries of persecution with deflection. Moral seriousness requires specificity. Justice requires naming crimes accurately. Peace requires confronting uncomfortable truths. To acknowledge that Christians are targeted does not require hatred of Muslims. To demand accountability does not require collective blame. But to refuse acknowledgment because it disrupts a preferred narrative is to abandon both truth and humanity. The question is not whether Muslims are also killed. The question is whether Christian deaths are being used as a bargaining chip in a moral shell game designed to avoid responsibility.

WHY CONDEMN THE AID COMING FOR CHRISTIANS?

1. The Moral Contradiction at the Heart of the Objection

The first question that must be confronted honestly is this: why would any morally serious person oppose humanitarian aid to civilians facing mass violence, regardless of their faith? Aid is not a theological endorsement; it is a response to human suffering. Condemning assistance to Christian communities under attack does not reduce violence, save Muslim lives, or advance justice—it merely withholds relief from victims. When opposition to aid becomes louder than condemnation of the killings themselves, priorities are exposed. Humanitarian intervention should never be framed as a zero-sum competition between communities, especially in a context where civilians of multiple faiths are being brutalized by armed groups.

2. The Missed Opportunity for Collective Advocacy

Nigeria’s insecurity has attracted rare international attention, and this moment could have been used constructively to amplify all civilian suffering. Instead of rejecting the framing of Christian victimhood outright, critics could acknowledge it while simultaneously presenting evidence of Muslim civilian casualties and calling for inclusive protection. International actors are capable of responding to multiple crises at once. Denial does not broaden concern; it narrows it. By rejecting the language of “Christian genocide” rather than supplementing it with documented accounts of Muslim suffering, critics inadvertently weaken the overall case for international engagement against terrorism.

3. Denial as a Strategy—and Its Consequences

There is a profound difference between contextualizing violence and denying it. When denial becomes the dominant response, it signals that controlling the narrative matters more than protecting lives. If Christians are being targeted in identifiable patterns—through church attacks, village raids, forced displacement, or selective killings—then disputing terminology should never take precedence over stopping the violence. The insistence on denial, especially when paired with hostility toward aid, creates the impression that reputational defense of a group or ideology has eclipsed compassion for victims. This perception, whether intended or not, damages trust and deepens communal suspicion.

4. If the Culprit Is the Same, Why Resist Intervention?

If both Christians and Muslims are suffering at the hands of the same armed actors—terrorist groups, criminal militias, or transnational extremists—then logic demands a united civilian front. Aid, investigations, and security interventions aimed at dismantling those networks should be welcomed, not resisted. Shielding perpetrators indirectly—by downplaying their impact on one community—undermines the safety of all communities. Terrorist violence does not respect religious boundaries; it exploits them. Any response that fragments civilian solidarity only strengthens the attackers.

5. The Responsibility of Muslims in Indigenous Communities

Muslims who are of the Indigenous tribes of Nigeria, like indigenous Christians, have deep historical, cultural, and communal ties to their regions. Their interests are aligned with peace, stability, and the protection of ancestral lands—not with violent actors who destabilize societies and invite external chaos. Standing against terrorism does not mean standing against Islam; it means standing for life, dignity, and coexistence. When indigenous Muslim voices openly support interventions that protect all civilians, they reclaim moral leadership and make it harder for extremists to masquerade as defenders of faith.

6. Aid Is Not the Enemy—Violence Is

Ultimately, the question is not whose suffering counts more, but whether suffering is allowed to continue unchecked. Humanitarian aid for Christians under attack does not negate Muslim suffering; it establishes a precedent that civilian lives matter. The appropriate response to selective attention is not obstruction, but expansion—demanding broader protection, deeper investigations, and comprehensive aid for all affected communities. Condemning aid aimed at one group risks normalizing cruelty. Supporting aid, while insisting on inclusivity, affirms a shared commitment to justice and human life above sectarian rivalry.

WHO, THEN, IS THE CULPRIT?

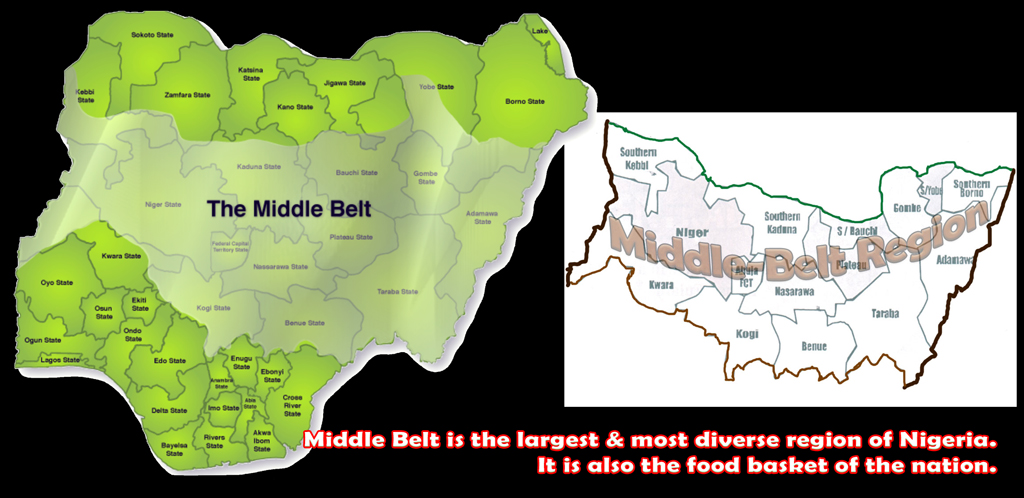

If Christians are not attacking Muslims as a religious collective, yet Muslims are also among those killed, then the perpetrators must be clearly and explicitly identified: armed extremist groups, criminal militias, terrorist organizations, or ideological movements that exploit religion for power and violence. Historical and contemporary data suggests the Islamist Fulani jihadists as the only group that fits this narrative; immigrants whose pristine motive from their first incursion to some territories that are constituent parts of what comprise present-day Nigeria was an Islamic jihad aimed at conquest and displacement of native people and institutions.

The refusal to distinguish between Islam as a faith and the Fulani violent actors who profess Islam harms everyone. It allows the Fulani settler immigrants and extremists to hide behind populations of indigenous ethnic groups and critics to be accused of bigotry for asking legitimate questions. Precision is not prejudice; it is the foundation of justice.

CONCLUSION: TRUTH IS NOT HATRED

Asking “Who is the culprit?” is not an act of hostility. It is an act of moral responsibility.

The lives of Christians lost to targeted violence cannot be erased by the rhetorical symmetry of the culprits. Nor can justice be achieved by pretending that all deaths arise from the same causes or carry the same intent.

If Muslims are killed, they deserve justice. If Christians are targeted for extermination, they also deserve justice, recognition and protection. These truths are not mutually exclusive. What is unacceptable is the weaponization of one tragedy to silence another. Truth demands clarity. Justice demands courage.

And, history will judge not only those who killed, but those who refused to ask who did it, and those who keep pretending not to know it’s the continuation of the genocidal campaign of the immigrant Islamist Fulani jihadists against the Native Indigenous Ethnic People and Christians of Nigeria.