By Steven Kefas

On November 1st, U.S President, Donald Trump issued what many are calling an unprecedented threat to a sovereign African nation. “If the Nigerian Government continues to allow the killing of Christians, the U.S.A. will immediately stop all aid and assistance to Nigeria, and may very well go into that now disgraced country, ‘guns-a-blazing,’ to completely wipe out the Islamic Terrorists who are committing these horrible atrocities,” Trump declared on his social media platform, adding that he has instructed the Department of War to prepare for possible action.

The response from Nigeria’s political class, thought leaders, and commentators has been predictably indignant. They warn of sovereignty violations, speak ominously of chaos and instability, invoke the specter of Libya and Iraq, and counsel caution about external military intervention. These concerns sound measured, reasonable, even patriotic.

But they ring hollow to the communities that have buried their dead by the hundreds while Nigeria’s government looked the other way.

The View from the Killing Fields

As someone who has spent over a decade documenting the ongoing massacre in Nigeria’s Middle Belt, interfacing directly with survivors, photographing mass graves, and listening to testimonies that would break the hardest heart, I can tell you this with certainty: the direct victims of these terrorist atrocities have reached a point where they no longer care where help comes from. When your government has abandoned you to slaughter, sovereignty becomes an abstract concept with little meaning.

Benjamin Badung, a 40-year-old father of five from Bangai district in Riyom Local Government Area of Plateau State, will not be pondering the geopolitical implications of American intervention. On May 20, 2025, his wife Kangyan was slaughtered by Fulani militants. He is raising five children alone, living in fear that the attackers will return to finish what they started. If American military action means his children stay alive and can thrive on their ancestral land, Benjamin Badung will not object on grounds of national sovereignty.

The survivors in Yelwata, Benue State, who I have visited 3 times since they buried 258 people, mostly women and children on June 14, 2025, are not concerned about the precedent of foreign military intervention. They watched their loved ones massacred over four hours of sustained attack while military barracks sat less than 20 miles away. They know their attackers. They know where the terrorists are camped, less than five miles away in Kadarko, Nasarawa state. Yet no arrests have been made. No camps have been bombarded. No justice has been served. If Trump’s threat galvanizes action against those who butchered their families, they will welcome it.

The people of over over 30 communities in Bokkos, who mourned over 200 dead on Christmas Day 2023, are not writing think pieces about the dangers of American military adventurism in Africa. They are wondering why their Christmas celebration became a massacre, why their churches were burned, why their government failed to protect them despite warnings of impending attacks.

The residents of Zikke in Miango, massacred while soldiers stationed less than four miles away remained motionless, are not worried about Nigeria’s international image. They are haunted by a more fundamental question: why did their own military refuse to defend them?

The peace loving people of Bindi in Tahoss district, Riyom LGA, a community of about a thousand people I have also visited and interacted with three times since the July 15 attack that left 27 people mostly women and children dead don’t really care if natural resources is stolen by America provided their farms become safer.

The list goes on. Community after community. Massacre after massacre. Mass grave after mass grave. And through it all, the Nigerian government has offered nothing but excuses, denials, and appeasement of the very terrorists carrying out these atrocities.

The Sudden Awakening of Nigeria’s Military

It is remarkable, and deeply cynical that in the 168 hours following Trump’s threat, the Nigerian military has suddenly flooded social media with posts about victories against terrorists in different parts of the country. Where was this energy for the past two decades? Why did it take an American president’s threat to spur action that should have been ongoing as a matter of national duty?

The message is unmistakable: Nigeria’s government is capable of fighting terrorism when sufficiently motivated. The capacity exists. The resources are available. What has been missing is political will. Trump’s statement has apparently provided that motivation in 168 hours, revealing what victims of these attacks have known all along, the failure to protect communities has been a choice, not an inability.

The Questions That Still Demand Answers

Even as the military scrambles to demonstrate competence in the Northeast and northwest, the fundamental questions about the Fulani jihadist insurgency in the Middle Belt remain unanswered.

The immediate past Chief of Defense Staff, General Christopher Gwabin Musa, stated during an August 2025 interview on Channels TV that the process of identifying and prosecuting terrorism financiers in Nigeria is ongoing, citing legal complexities. But who are these financiers? Why, after two decades of attacks involving sophisticated weapons and coordinated operations across multiple states, has not a single major financier been publicly identified, arrested, and prosecuted?

Where do the Fulani ethnic militants operating in the Northwest and Middle Belt acquire military-grade weapons? These are not crude hunting rifles; survivors describe AK-47s, AK-49, RPGs, general-purpose machine guns, and in some cases, anti-aircraft weapons. Such arsenals require supply chains, logistics, and financing. Yet the Nigerian government claims inability to trace these obvious channels.

How is it possible that terrorists appear in public, sometimes armed and in the presence of security agents, without arrests? Recent videos from Guga Ward in Bakori Local Government Area of Katsina State show armed Fulani militants attending “peace talks” with weapons visible, surrounded by traditional rulers and, disturbingly, security personnel. In any functional state, such gatherings would result in mass arrests. In Nigeria, they result in photo opportunities.

Why is the Nigerian National Security Adviser, Mallam Nuhu Ribadu, bent on appeasing Fulani terrorists instead of allowing the military to treat them as the terrorists they are? His alleged championing of peace deals that demand no disarmament, no accountability, and no cessation of violence represents either profound incompetence or something more sinister.

The Martyr They Created: General Christopher Musa’s Warning

Perhaps the most telling aspect of this entire crisis is what happened to General Christopher Musa. Just five days before his removal as Chief of Defence Staff, General Musa issued a stark warning to Nigerians about peace deals with terrorists.

“We therefore urge everyone: do not make peace with them. We do not support these bandits or any peace agreement with them. If they genuinely want to stop, they should lay down their weapons and surrender. If they surrender, we will take them into custody, screen and investigate them thoroughly; that’s the proper approach,” General Musa stated clearly.

He continued with even more pointed language: “But sitting down with a bandit and asking ‘Why did you pick up a gun?’ is pointless. It’s driven by greed, and greedy people will not give up. They will never stop. So there should be no truce with them.”

This was a military leader articulating sound counterterrorism doctrine: no negotiations with active terrorists, demand for unconditional surrender, thorough screening and investigation of those who lay down arms, and absolute rejection of the peace deal charade that has characterized Nigeria’s approach to both Boko Haram and the Fulani militants insurgency.

In the same month, General Musa issued a directive to troops to eliminate any terrorist killing civilians and destroying property nationwide. This was exactly the kind of aggressive posture needed to confront groups that have operated with impunity for two decades.

The response from certain Northern elites and Islamic clerics was immediate and hostile. They objected vehemently to this directive, advocating instead for continued peace deals with terrorists. Shortly thereafter, General Musa was removed from his position.

The message sent was chilling: a Chief of Defence Staff who takes a hard line against Islamist terrorists will not be tolerated. Those who advocate for crushing terrorist groups rather than accommodating them will definitely be removed. We saw it happen to Gen Ihejerika at the peak of the Boko Haram insurgency in the northeast. The political will to confront the Fulani jihadist insurgency does not exist at the highest levels of Nigeria’s government, and anyone who attempts to act decisively will be neutralized.

General Musa’s removal, following immediately after his public rejection of terrorist appeasement, reveals the fundamental rot at the core of Nigeria’s counterterrorism strategy. It explains why, despite a capable military that has successfully conducted peacekeeping operations in Sierra Leone, Liberia, and other conflict zones, Nigeria cannot or will not crush armed groups terrorizing its own citizens.

The Elite Panic vs. The Victims’ Reality

The panic among Nigeria’s political and intellectual class over Trump’s threat is instructive. Where was this passionate defense of Nigerian sovereignty when communities were being wiped out and some occupied by terrorist elements? Where were the think pieces and television appearances when churches were being burned and farmlands destroyed? Where was the outrage when peace deals legitimized terrorists?

For two decades, Nigeria’s elites have been largely silent as communities in the Middle Belt faced systematic extermination. They characterized genocide as “farmer-herder clashes.” They blamed victims for not “accommodating” their killers, they blamed climate change. They counseled patience and reconciliation while bodies piled higher.

Now, suddenly, they have found their voices, not to demand protection for vulnerable communities, but to object to the prospect of someone else providing that protection.

This is not patriotism. This is complicity masquerading as principle.

What Trump’s Threat Reveals

Whether President Trump follows through on his threat or not, his statement has accomplished something the Nigerian government has failed to achieve in two decades: it has forced a conversation about the true nature of violence against Christians and other religious groups in Nigeria.

The euphemisms are no longer working. The world is no longer accepting “farmer-herder clashes” as explanation for systematic religious persecution. The fiction that these are spontaneous conflicts over resources has been exposed. The pretense that Nigeria’s government is doing everything possible to protect all citizens has collapsed.

Trump’s threat as crude as it may sound to diplomatic ears speaks a language that Nigeria’s government apparently understands: consequences. For years, international partners issued strongly worded statements, expressed concern, called for dialogue. Nothing changed. Now, facing potential military intervention and aid cutoffs, the Nigerian military suddenly discovers operational capacity it has denied possessing for years.

The Path Nigeria Must Take

If Nigeria’s government wishes to avoid the humiliation of foreign military intervention on its soil, the solution is straightforward: do your job. Protect your citizens. Crush the terrorists. End the appeasement.

Specifically:

Remove Nuhu Ribadu as National Security Adviser and replace him with someone committed to defeating terrorism rather than accommodating it.

Reinstate General Christopher Musa’s directive to eliminate terrorists killing civilians, and ensure military commanders face consequences for failure to act.

Officially designate armed Fulani militia groups as terrorist organizations and prosecute them accordingly under Nigeria’s terrorism laws.

Launch coordinated military operations to clear terrorist camps in the Middle Belt, starting with all known locations.

Arrest and prosecute terrorism financiers instead of citing endless “legal complexities” as excuse for inaction.

End all peace deals with active terrorist groups and demand unconditional surrender as the only acceptable path for those who wish to lay down arms.

The authorities should arrest and prosecute Sheikh Ahmed Gumi and other clerics who defend and justify atrocities committed by terrorists, individuals the government and media have euphemistically labeled as “bandits.”

Provide justice and reparations for the millions of victims who have lost family members, homes, and livelihoods.

These are not impossible demands. They are basic functions of government. That they seem radical in the Nigerian context reveals how far the government has strayed from its fundamental duty to protect citizens.

A Message to Nigeria’s Elites

Your sudden concern about sovereignty and stability would be more credible if you had shown similar concern when your fellow citizens were being massacred. Your warnings about the dangers of foreign intervention would carry more weight if you had demanded domestic action when it could have prevented this crisis.

You cannot remain silent while communities are exterminated and then clutch your pearls when someone else threatens to act. You cannot characterize genocide as economic conflict and then object when others call it what it is. You cannot accommodate terrorists for two decades and then suddenly discover principles when faced with consequences.

The victims of Fulani jihadist terrorism are not impressed by your geopolitical analysis. They are not moved by your concerns about precedent. They are not comforted by your counsel of patience. They have been patient for twenty years while you did nothing.

If you do not want foreign intervention in Nigeria, then demand that your government intervene to protect Nigerians. If you object to Trump’s threat, channel that energy into demanding that Tinubu’s administration crush the terrorists. If you care about sovereignty, insist that Nigeria exercise sovereignty by defending all its citizens, not just those whose deaths are politically inconvenient to acknowledge.

Conclusion: When Survival Trumps Sovereignty

I do not know if President Trump will follow through on his threat. I do not know if American military action in Nigeria would succeed or fail, bring peace or chaos. What I know is this: for communities that have buried their dead by the hundreds while their government looked away, the calculation is simple.

They have tried trusting their government. Their government failed them.

They have tried appealing to national authorities. National authorities ignored them.

They have tried documenting atrocities to force action. The documentation was dismissed as exaggeration.

They have tried international advocacy. It was characterized as unpatriotic.

Now, finally, someone with real power is threatening consequences for their government’s failure to protect them. And Nigeria’s elites are upset, not at the government that abandoned these communities to slaughter, but at the foreign leader threatening to act where Nigeria will not.

The people of the Middle Belt are watching this reaction, and they are drawing conclusions about who their real enemies are. It is not just the terrorists pulling triggers. It is also those who create the conditions for those triggers to be pulled with impunity, and those who object more strenuously to the prospect of justice than to the reality of genocide.

Trump’s threat may be crude, it may be controversial, it may be problematic in numerous ways. But to the husband who buried his wife, to the community that buried its children, to the survivors waiting for the terrorists to return, it is something else entirely: it is acknowledgment that their lives matter, that their suffering is seen, and that someone, somewhere, is willing to act.

That is more than Nigeria’s government has given them in twenty years.

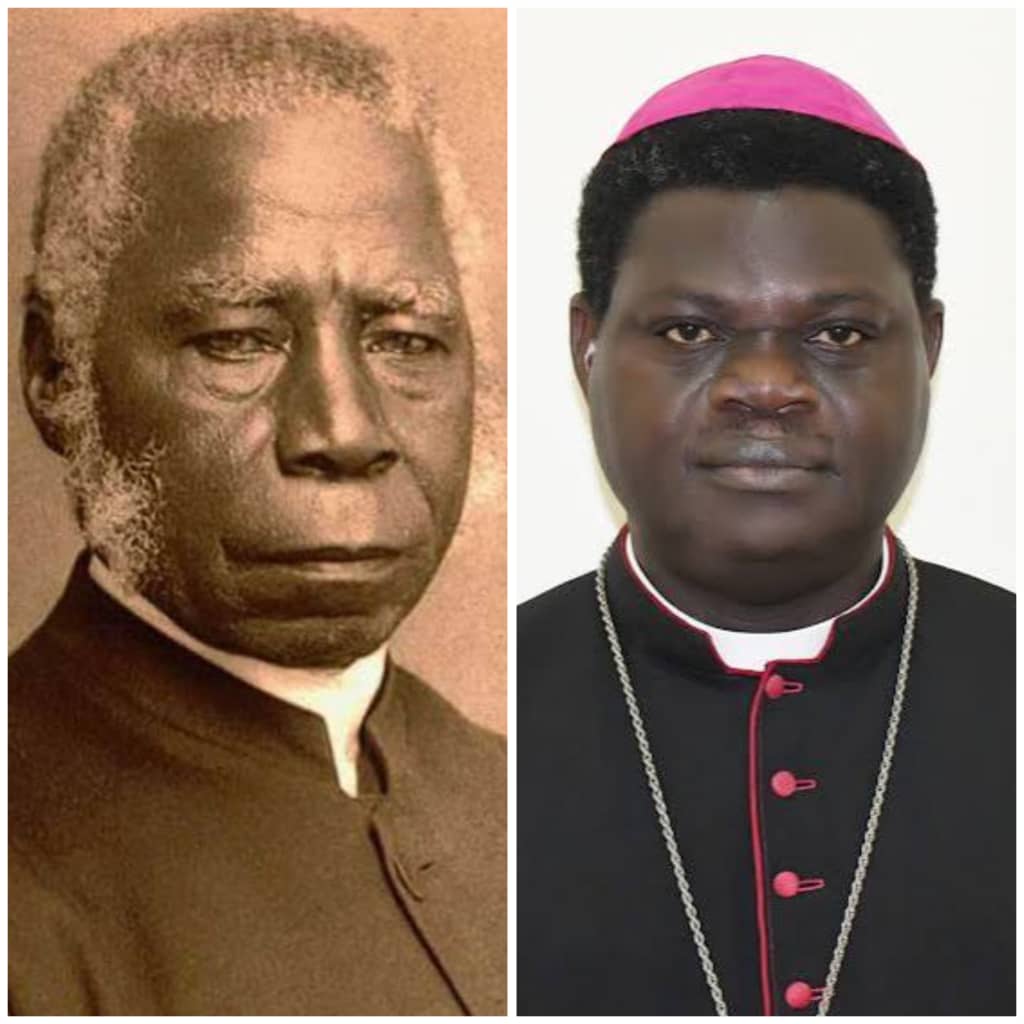

Picture: cooking pots abandoned by fleeing residents during Islamic Fulani terrorists attack in Januwa village, Yangtu Development Area, Taraba state. Credit: Steven Kefas

…Steven Kefas is an investigative journalist, Senior Research Analyst at the Observatory for Religious Freedom in Africa, and Publisher of Middle Belt Times. He has documented religious persecution and forced displacement in Nigeria’s Middle Belt for over a decade.